February 12, 2014

US Economy: Stealth Inflationary Pressures Are Not Yet Priced Into Markets

Posted in Banking, Capital, CBO, Congressional budget office, deflation, Economic Growth, Economy, emerging markets, establishment survey, Europe, Finance, GDP, Inflation, investment advisor, investment banking, investments, job market, labor force, Labor Market, obamacare, payroll tax reductions, Robert Barone, small business, Unemployment at 5:18 PM by Robert Barone

In countries where central banks are printing money, such as the US, UK, eurozone, and Japan, deflation is the fear. On the other hand, inflation is high in countries where central banks have followed more traditional policies, like Brazil (official inflation 5.9%), India (11.5%), Indonesia (8.4%), and Turkey (7.4%). One explanation is the carry trade. Because the central banks of the developed world promised low rates for the long term, the liquidity created by those central banks found its way into the economies of the emerging markets (EM) (read: borrow at low interest rates, invest at high ones). Unfortunately, most of those funds did not find their way into capital investment in those markets, but was instead used for consumption, which has played havoc with EM trade balances. When the demand side (usually measured by GDP) outstrips the supply side (potential GDP), inflation occurs. Now that the bubble in EM countries, caused by excess liquidity in the developed world, is starting to burst — investors no longer believe the carry trade will last much longer — what will become of all of that liquidity?

On February 4, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), a supposed non-partisan government agency, released a shocking report, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2014 to 2024,” projecting that over the next 10 years the Affordable Care Act, commonly referred to as Obamacare, would reduce future employment rolls by more than 2.3 million. Overlooked in that report is the CBO’s projection that “potential” GDP in the US will be much slower over the next 10-year period than it has averaged since 1950; this in an age of innovation where rapid change is considered normal. The CBO says that “changes in people’s economic incentives caused by federal tax and spending policies set in current law are expected to reduce the number of hours worked…” and “that estimate largely reflects changes in labor hours worked owing to the ACA [Affordable Care Act].”

In the US, if the current gap between real GDP and potential GDP closes (and the so-called “slack” in the economy disappears as the CBO projects it will), then, just like in the EMs, any growth on the demand side of GDP above potential GDP, ends up, by definition, as inflation.

There are a many measures that indicate that the economy is much closer to its potential than is generally assumed. One such measure is the fact that, despite record levels of cash flow (used mainly for stock buybacks or dividends), for the past five years, corporations have not reinvested in their plant and equipment. According to David Rosenberg (Gluskin-Sheff), the average age of the capital stock in the US is almost 22 years, an average not seen since 1958. Given the fact that the cost of capital is near an all-time low, there is something holding back such investment. Rosenberg speculates that it is likely found in overregulation and the uncertainty regarding tax policy. An old and aging capital stock implies a much lower growth rate of potential GDP than in the past when the capital stock was younger.

The second issue is the labor force. While the December and January Establishment Survey disappointed the markets (December’s survey reported 75,000 jobs added; January saw a gain of 113,000), nobody is talking about the Household Survey. This is the survey from which the “official” unemployment rate is calculated. While more volatile that the Establishment Survey, the Household Survey showed gains of 143,000 jobs in December and a whopping 638,000 in January. When combined with other surveys (NFIB) which show that 23% of small businesses have at least one open position that they cannot fill (a six-year high according to Rosenberg), and that there is a sustained uptrend in voluntary quits, it would appear that the Establishment Survey is the outlier and that the labor market is quite tight.

If, indeed, the CBO is correct and potential GDP growth will slow over the next 10 years due to Obamacare, a tight labor market in conjunction with old capital stock will only exacerbate that situation. Since the financial crisis, the unemployment rate has fallen from 10.0% in October ’09 to 6.6% in January ’14, a 3.4 percentage point decline. During that period of time, the annual GDP growth rate has been about 2.4%. After the recession of the ’90s, to get the unemployment rate to fall 3.4 percentage points (from 7.8% to 4.4%), it took an annualized GDP growth rate of 3.7%. The lower GDP growth required to reduce the unemployment rate implies that the gap between actual and potential GDP is either small or nonexistent.

The aging of the capital stock, lack of new investment, and the tightening labor market indicate that resources are in short supply, which means that there is a strong probability that any semblance of robust economic growth will be accompanied by inflation. Adding to such pressure is the liquidity sloshing around the EM world. If it finds its way home, as appears to be happening, unless much of it goes into new capital formation (which is unlikely given the current regulatory and tax regimes), we are likely to see growing inflationary pressures much sooner than is currently priced into the financial markets.

February 4, 2014

Existing Public Policy Fosters a Growing Income Gap

Posted in business, Business Friendly, Dodd Frank, Economic Growth, Economy, Federal Reserve, Finance, income gap, Inflation, lending, Public Policy, Quantitative Easing, small business at 9:12 PM by Robert Barone

There is no doubt that the gap between the rich and the middle class and poor has widened in recent years. And the most recent studies confirm a continuation of that trend with capital gains playing a major role.

What is ironic is that public policies — some long practiced, some new, — contribute significantly to the problem. Recognizing and fixing such policy issues, however, is easier said than done.

In this post, I will discuss three such policies: 1) The asset inflation policies of the Fed; 2) The policy that significantly understates inflation; and 3) The policies that strangle lending to small business. There are many other public policies, such as work disincentives, that also have an impact, but I’ll discuss them another time

Fed Policy

Since the financial crisis, the Fed, through its “quantitative-easing” policies, has relied upon the “wealth effect” via equity asset price inflation to combat the so-called deflationary forces that had built up in the economy.

Each time a QE policy ended, there was a big decline in equity prices. Those declines prompted another round of QE.

As indicated above, capital gains have played a major role in the recent growth of the income gap. Those gains also played a major role in the dot.com and subprime bubbles of the recent past.

Inflation

In his Jan. 29 missive to clients, David Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff, a wealth-management firm, said that “if we were to replace the imputed rent measure of CPI (consumer price index) with the actual transaction price measure of the CS-20 [Case Shiller home price index], core inflation would be 5.3% today, not 1.7% as per the ‘official’ government number…”

John Williams (www.shadowstats.com) indicates that, using the 1990 CPI computation, inflation in the U.S. was 4.9% in 2013; using the 1980 computation method, it was 9.1%.

Those of you old enough may remember that in 1980 the then new Fed Chairman, Paul Volker, began to raise interest rates to double-digit levels to combat an inflation that was not much higher than the 9.1% of today (if the 1980 methodology is used).

Over the years the Bureau of Labor Statistics has changed the computation method for CPI, in effect, significantly biasing it to produce a much lower inflation rate.

In a post I wrote last September (“Hidden Inflation Slows Growth, Holds Down Wages,” TheStreet.com, 9/13/13), I showed how the growth of wages earned by middle-class employees has hugged the “official” inflation trend.

If that “official” inflation trend understates real inflation by 3% per year (the difference between Williams’ computation using the 1990 methodology and 2013’s “official” rate is 3.1%), over a 20-year period, the real purchasing power of that wage would fall by more than 80%.

That helps to explain why both husbands and wives must work today, why the birth rate is falling and why the income gap is widening.

Once again, changing the inflation measurement problem is easier said than done. In the U.S., Japan, the U.K and the eurozone, debt levels are a huge issue. Lower inflation rates keep interest rates low, allow new borrowing (budget deficits) at low rates and keep the interest cost of the debt manageable (at least temporarily).

Also, a low official rate keeps the cost-of-living adjustments for social programs — Social Security, Medicare and government pensions — low. As a result, Social Security, Medicare and pension payments are significantly lower than they otherwise would be. Returning to the older, more accurate inflation measures would truly be budget busting.

Constraints on Small Business Lending

One of the reasons that the economic recovery has been so sluggish is the inability for small business to expand. Since the financial crisis, much of the money creation by the Fed has ended up as excess reserves in the banking system (now more than $2.3 trillion).

Small businesses employ more than 75% of the workforce. So, why aren’t banks lending to small businesses?

In prior periods of economic growth, especially in the 1990s and the first few years of the current century, it was the small and intermediate-sized banks that made loans to small businesses in their communities.

Today, for many of the banks that survived the last five years, there are so many newly imposed reporting and lending constraints (Dodd-Frank) and such a fear of regulatory criticism, fines or other disciplinary action that these institutions won’t take any risk at all. In earlier times, the annual number of new community bank charters was always in the high double digits.

But, since 2011, the FDIC has approved only one new bank charter that wasn’t for the purpose of saving an existing troubled bank. Only one!

In effect, the federal regulators now run the community banking system from seats of power in their far away offices.

Small businesses cannot grow due to the unavailability of funding caused by overregulation and government imposed constraints. This holds down the income growth of much of the entrepreneurial class and is a significant contributor to income inequality. Of the policies discussed in this post, this would be the easiest to change.

Conclusion

There is definitely a growing income gap, but, much of it is the result of public policy. New elections or new legislation won’t fix these policies. The first step is recognition. But, as I’ve pointed out, many of these policies are rooted in the fabric of government.

There is little desire on the part of those comfortably in power to recognize them, much less to initiate any changes.

Robert Barone (Ph.D., economics, Georgetown University) is a principal of Universal Value Advisors, Reno, a registered investment adviser. Barone is a former director of the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco and is currently a director of Allied Mineral Products, Columbus, Ohio, AAA Northern California, Nevada, Utah Auto Club, and the associated AAA Insurance Co., where he chairs the investment committee. Contact Robert Barone or the professionals at UVA (Joshua Barone and Andrea Knapp)

are available to discuss client investment needs. Call them at 775-284-7778.

Statistics and other information have been compiled from various sources. Universal Value Advisors believes the facts and information to be accurate and credible but makes no guarantee to the complete accuracy of this information.

January 14, 2014

Why Gold Prices Dropped in 2013

Posted in Banking, Big Banks, Economic Growth, Economy, Europe, Federal Reserve, Finance, Foreign, gold, Inflation, interest rates, investment advisor, investments, Robert Barone at 6:39 PM by Robert Barone

Most seasoned investors have some allocation to precious metals in their portfolios, most often gold. They believe that such an allocation protects them, as it is a hedge, or an insurance policy, against the proliferation of paper (fiat) money by the world’s largest central banks. Fiat money is not backed by real physical assets. In concept, I agree with this sentiment. Most investors who invest in precious metals ETFs, such as the SPDR Gold Trust ETF (NYSEARCA:GLD), through the supposedly regulated stock exchanges (“paper gold”) believe that they actually have a hedge against future inflation. In what follows, I will try to explain why they may not, and why their investments in paper gold may just be speculation.

On February 5, 1981, then Fed Chairman Paul Volcker said that the Fed had made a “commitment to a monetary policy consistent with reducing inflation…” Contrast that with the statement of outgoing Fed Chairman Bernanke on December 18, 2013: “We are very committed to making sure that inflation does not stay too low…”

During 2013, the price of gold fell more than 28% (from $165.17/oz. to $118.36/oz.) despite the fact that other assets like real estate and equities each rose at double-digit rates. It is perplexing that the price of the hedge against inflation is falling in the face of a money-printing orgy at all of the world’s major central banks. Despite the fact that these central banks have fought the inflation scourge for half of a century, suddenly they have all adopted policies that espouse inflation as something desirable. The fall in the price of gold is even more perplexing because there are reports of record demand for physical gold, especially in Asia, and that some of the mints can’t keep up with the demand for standardized product. In his year-end missive, John Hathaway of Tocqueville.com says that “the manager of one of the largest Swiss refiners stated that after almost doubling capacity this year, ‘they put on three shifts, they’re working 24 hours a day…and every time [we] think it’s going to slow down, [we] get more orders…70% of the kilo bar fabrication is going to China.'”

One would also think that the price of gold should be rising because of a growing loss of confidence in fiat currencies. Here are some indicators:

The growing interest in Bitcoin as an alternative to government-issued currencies. One should ask, why did the price of Bitcoin rise from $13.51 on December 31, 2012 to $754.76 on December 30, 2013 while the price of gold fell? As you will see later in this essay, the answer lies in leverage. The gold market is leveraged; Bitcoin is not (at least, not yet).

The volatility that the Fed has caused in emerging market economies by flooding the world with dollars at zero interest is another reason the price of gold should be rising. The Fed’s announced zero-rate policy with a time horizon caused huge capital flows into emerging market economies by hedge funds looking for yield. The inflows caused disruption to the immature financial systems in those emerging markets. And then, with the utterance of a single word, “tapering,” all of the hedge funds headed for the exits at once. The Indian rupee, for example, which was trading around 53 rupees/dollar in May 2013, fell to 69 near the end of August, a 30% loss of value. Such behavior has stirred up new interest on the part of major international players (China, Russia) to have an alternative to the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Don’t dismiss this as political posturing. It is based on irresponsible Fed policy in its role as the caretaker of the world’s reserve currency. As the world moves toward an alternative reserve currency, the dollar will weaken significantly relative to other currencies, and, theoretically, to gold (and even Bitcoin).

The loss of confidence on the part of some sovereign nations that the gold they have stored in foreign bank vaults is safe. Two examples immediately come to mind: Venezuela and Germany. In August of 2011, the President of Venezuela, Hugo Chavez, demanded that the London bullion banks that were holding Venezuela’s gold ship it to Caracas. (Again, don’t dismiss this as political posturing.) Despite the fact that the shipment could have been carried on a single cargo plane, it took until late January 2012 (17 months), for the London banks to completely comply. One should wonder why. Then, the German Bundesbank asked for an audit of its gold holdings at the Fed. One knows how the Fed has resisted audits from Congress, so why should a request from a German bank meet with any different result? After political escalation, a German minister was permitted to see a room full of gold at the New York Fed. In early 2013, the Bundesbank publicly announced that its intent was to repatriate its gold from the vaults in Paris, London, and New York. We have now learned that it will take seven years for the New York Fed to ship the gold earmarked as belonging to Germany in the Fed’s vaults. One should wonder why such a long delay.

In the face of all of this — unparalleled money printing, the rise in the prices of real estate and equities in 2013, and the creeping suspicions regarding the real value of fiat currencies — how is it that the price of gold fell 28% in 2013? The answer lies in leverage and hypothecation, the modus operandi of Wall Street, London, and financiers worldwide. The paper gold market, the one that trades the ETFs such as the SPDR Gold Trust, is 92 times bigger than the physical supply of gold according to Tocqueville’s John Hathaway. Think about that. It means that each physical ounce of gold that actually exists has been loaned, pledged, and re-loaned 92 times on average. Each holder in the paper gold market thinks that the ounce of paper gold held in the brokerage account is backed by an ounce of real gold. But there are, on average, 92 others who apparently have a claim on the same real, physical ounce.

The answer to the question, why did gold fall 28% in 2013 when, theoretically, it should have risen, is that Wall Street, London, and hedge funds have turned the paper gold market into a market of speculation, where the price rises or falls, not based on the purchasing power of currencies (the hedging characteristic of gold), but on such things as whether or not the Fed will taper, what impact Iranian nuclear talks will have on oil flows, if the interest rates in the eurozone periphery are likely to rise or fall, etc.

In my next article, I will explain how all of this occurred, and what investors who want to hedge and not speculate should do.

Robert Barone (Ph.D., economics, Georgetown University) is a principal of Universal Value Advisors, Reno, a registered investment adviser. Barone is a former director of the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco and is currently a director of Allied Mineral Products, Columbus, Ohio, AAA Northern California, Nevada, Utah Auto Club, and the associated AAA Insurance Co., where he chairs the investment committee. Barone or the professionals at UVA (Joshua Barone, Andrea Knapp and Marvin Grulli) are available to discuss client investment needs.

Call them at 775-284-7778.

Statistics and other information have been compiled from various sources. Universal Value Advisors believes the facts and information to be accurate and credible but makes no guarantee to the complete accuracy of this information.

December 30, 2013

8 U.S. business predictions for 2014

Posted in Auto Industry, business, Economic Growth, Economy, Finance, GDP, gold, government, Housing Market, Inflation, interest rates, investment advisor, investment banking, Labor Market, Manufacturing, Robert Barone, Unemployment, Wall Street at 8:45 PM by Robert Barone

The holiday season is the traditional time of year to prognosticate about the upcoming year. But, before I start, I want to make a distinction between short-term and long-term forecasts.

Long-term trends are just that, and they unfold slowly. And, while I have great concerns about the long-term consequences of inflation, the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency, the bloated Fed balance sheet and resulting excess bank reserves, and the freight train of unfunded liabilities which will impact the debt and deficit, because these are long-term issues and simply don’t appear overnight, I do not believe there is anything contradictory about being optimistic about the short-term.

With that caveat, here are my predictions for 2014:

1. Real GDP will grow faster in 2014 (3.5%): The “fiscal drag” that caused headwinds for the economy has now passed with the signing of the first budget in four years in mid-December. Since 2009, governments at all levels have been shedding jobs. But, that has now all changed. The November jobs reports show that employment at all levels of government has turned positive.

No matter your view of the desirability of this for the long-term, in the short-term, those employees receive paychecks and consume goods and services. I predict the real gross domestic product growth rate will be more than 3.5 percent in 2014.

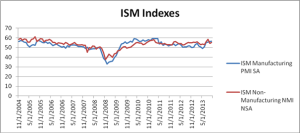

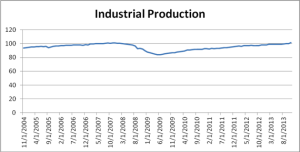

2. Manufacturing and trade are healthy and will get better in 2014: The Institute for Supply Management’s indexes, both manufacturing and non-manufacturing, are as high or higher than they were in the ’05-’06 boom. In November, industrial production finally exceeded its ’07 prior peak level.

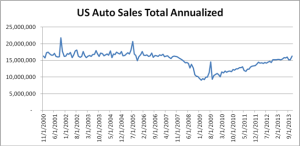

Auto sales today are as frothy as they were in the pre-recession boom, and auto sales in the holiday buying period are destined to surprise to the upside. Online sales in the weekend before Christmas overwhelmed both UPS and FedEx, causing many gifts to be delivered on the 26th.

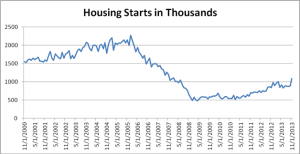

3. Housing, while not near its old bubble peak, has turned the corner: Part of the reason the economy is not overheating is housing. While November’s housing starts surprised to the upside, they still only represent 53 percent of their bubble peak. Nevertheless, because new home construction has been in the doldrums for the past six years, the resurgence evident in the economy has pushed the median price of homes to the point where many homeowners, who were underwater just a couple of years ago, can now show positive home equity on their balance sheets

While interest rates have risen and may be a cause for concern for housing, they are still very low by historic standards, and we have a Fed that, on Dec. 18, recommitted to keeping them down for a period much longer than the market ever anticipated.

4. The unemployment rate will end 2014 somewhere near 6%: Because the popular unemployment index is a lot higher today than it was in the ’05-’06 boom (7 percent vs. 5 percent), the popular media assumes that the labor markets are still loose. But, demographics and incentives to work have changed over the past seven years.

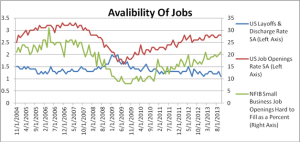

The labor sub-indicators imply much tighter labor conditions than the traditional unemployment index would lead one to believe. Recent data for nonfarm payrolls are equivalent to their monthly numbers in ’05-’06. Weekly new jobless claims are in a steep downtrend. The sub-indexes for layoffs and discharges are lower than they were in ’05-’06. And hard-to-fill-position and job-opening subindexes are in definite uptrends and are approaching ’05-’06 levels. As a result, expect a steady decline in the unemployment rate in 2014.

5. Investment in new plant & equipment will rise in 2014: For the past 5 years, large-cap corporations have hoarded cash and have not reinvested in their businesses. As a result, because equipment and technology is older, labor productivity has stagnated. This is one reason for the strong labor market. In 2014, I predict there will be an upturn in the reinvestment cycle. Beneficiaries will be technology companies and banks.

6. Inflation will be higher in 2014, both “officially” and in reality: While every individual player in the financial markets knows that everyday prices are rising, each espouses the Fed’s deflation theme, perhaps only to play along hoping the Fed will continue printing money.

Are we to believe that the jump of retail sales in October of 0.6 percent followed by 0.7 percent in November were all without price increases as the Bureau of Labor Statistics says? The “official” consumer price index says that airline fares have not increased despite the 18 percent growth of airline revenues in 2013 (bag check fees, etc.)? Should we believe that double-digit revenue growth rates at restaurants are volume-only and we are just eating more? I don’t know what the actual rate of inflation is, but it sure feels like it is higher than 5 percent. In 2014, it will be even higher than that.

7. Equity markets will rise in 2014: The fiscal headwinds are behind us; industrial production and sales are strong; housing is healing, the rise in home prices have generally raised consumer confidence; there appears to be the beginning of an upturn in the capital investment cycle; and, most important, the labor markets are strong. Any equity market corrections should be bought. Meanwhile, longer-duration bonds should be avoided unless there is an accompanying hedge instrument.

8. Gold — it should rise in 2014, but this is a tricky market: Every indicator points to a rise in the price of gold, especially since all of the world’s major central banks are printing money at record rates. But, contrary to logic, the price of gold has fallen in 2013 by nearly 30 percent.

The reason behind this lies with leverage and hypothecation — getting a loan using collateral — in the gold market. Once again, Wall Street has discovered that money could be made by leveraging; and the paper gold market is about 100 times larger than the physical market. When you have that kind of leverage, collusion, price fixing, or just plain panic can quickly move markets.

As inflation is recognized, the price of gold (both physical and paper) should rise. In a healthy economic year, as I predict for 2014, a collapse in the paper gold market is unlikely, and perhaps the price of gold will rise in response to rapidly expanding fiat money. But beware. The only safe gold is what you can hold in your hand.

December 27, 2013

Part II: The Long-Term Outlook – Even a Strong Economy Doesn’t Change the Ultimate Outcome

Posted in business, debt, Economic Growth, Economy, Europe, Finance, Foreign, Inflation, investment advisor, investment banking, investments, Markets, National Deblt, Robert Barone at 4:46 PM by Robert Barone

If you’ve read Part I of this year end outlook, you know that it is our view that the underlying private sector is healthy and, except for the fact that the real rate of inflation is much faster than the ‘official’ rate, we could well have a short period of prosperity.

Unfortunately, our long-term outlook is not as sanguine as our short-term view. The eventual recognition of the inflation issue, the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency, the bloated Fed balance sheet and the resulting excess bank reserves, and the freight train of unfunded liabilities and its impact on the debt and deficit are issues that have large negative long-term consequences. Remember, the long-term unfolds slowly, and we don’t expect that we will wake up one day to find that all has changed. Still, the changes discussed below could very well take place over the next decade, and investors need to be prepared.

The Dollar as the Reserve Currency

The dollar is currently the world’s reserve currency. Most world trade takes place in dollars, even if no American entity is involved. Because world trade has rapidly expanded over the past 20 years, more dollars have been needed than those required for the U.S. economy alone. As a result, the U.S. has been able to run large deficits without any apparent significant impact on the dollar’s value relative to other major currencies. Any other country that runs a large deficit relative to their GDP suffers significant currency devaluation. Current policy in Japan is a prime example. A weakening dollar has implications for the prices of hard assets.

In addition, the Fed’s policy of Quantitative Easing (essentially money printing) has disrupted emerging market economies. Zero rates and money creation caused hedge fund managers to leverage at low rates and move large volumes of money offshore to emerging nations where interest rates were higher. The initial fear of “taper” in May and June caused huge and sudden capital outflows from those countries resulting in massive economic dislocation in those markets. In India, for example, the Rupee was pummeled as the hedge fund investors, fearing that interest rates were about to suddenly rise, all tried to unwind their Rupee investments at the same time. And now that ‘taper’ has officially started and longer-term rates are expected to rise, these issues will continue. Those countries have all taken defensive measures. India, for example, imposed taxes on gold imports, which has impacted the gold markets but has reduced India’s balance of payments deficit.

As a result of such tone deafness on the part of the Fed, and because there now appears to be enough dollars in the world for the current level of trade, the international appetite for U.S. dollars is clearly on the wane. Japan and China, the two largest holders of Treasury debt, have recently reduced purchases. Most emerging market nations and large players like Russia and China have vocally called for an alternative to the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. This movement is alive and well.

The Fed’s Balance Sheet

As the economy expands, the size of the Fed’s balance sheet and the level of excess bank reserves will become a problem. There are $2.3 trillion of bank reserves in excess of what are ‘required’ under the law and regulations. (Required reserves for the U.S. banking system are $.067 trillion; so, the system has 34x more reserves than it needs.) Under ‘normal’ conditions, and the way the system was designed to work, if the economy got too hot, the Fed could sell a small amount of securities out of its portfolio which would reduce bank reserves to the point where banks would have to ‘borrow’ from the Fed. Because bankers are hesitant to do that, and because the Fed could raise the ‘discount’ rate, the rate charged for the borrowings, the Fed could control new lending and thus the economic expansion. This isn’t possible today as the Fed would have to sell $2.2 trillion to cause banks to have to borrow. Such a volume of sales would likely cause a crisis in the financial system, or even collapse. Today, the only way the Fed has to stop the banks from lending is to pay them not to lend – this is exactly the opposite of the intent of the original legislation and the opposite of how the Fed has worked for most of its 100 year history.

Furthermore, given the growing lack of confidence in the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, if fiscal budget deficits grow in the future, the Fed may end up as the major lender (i.e., lender of last resort) for the U.S. Treasury. That simply means more money creation.

Unfunded Liabilities-

The U.S. Treasury officially recognizes $85 trillion as the amount of unfunded liabilities of the Federal Government. Other professionals set this number near $120 trillion. For comparison, the annual U.S. GDP is about $16 trillion. The budget deficit reported in the media is a cash flow deficit (tax collections minus expenditures). The budget deficit doesn’t include promises made for future payments (Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, government pensions) which have been running between $4 and $5 trillion annually for the past few years. These amounts simply get added to the ‘unfunded’ liability number.

As the population ages, these payments will have to be made, and the budget may become overwhelmed. (You see the relevance of the remark made above about the Fed being the lender of last resort for the Treasury.) This is the heart of the debate about ‘entitlements’ that has been front and center for the past decade.

Solutions (none of which you will like)

Philipp Bagus is a fellow at the Ludwig von Mises Institute in Europe. He is well known in Europe for his work on financial issues there. In a recent paper, Bagus says that there are several possible ways out of the current money printing predicament. Any one or a combination is possible. We have put them in an order of most likely to least likely to be used:

- Inflation – this is the natural outcome of printing money;

- Financial Repression – this is current Fed policy; savers and retirees bear a disproportionately large burden as inflation eats at their principle but there is no safe way to earn a positive real rate of return;

- Pay Off Debt – this means much higher levels of taxation, and is definitely a real possibility. In Europe, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has proposed a one-time 10% wealth tax. As the unfunded liabilities push up the federal deficit, expect such proposals in the U.S.;

- Bail-In – In ’08-’09 we saw ‘bail-outs’ where the government saved GM, Chrysler, AIG and the Too Big to Fail banks by buying stock or otherwise recapitalizing them. A ‘bail-in’ refers to the financial system. Banks and other depositories have liabilities called deposits. The depositors do not consider themselves ‘lenders.’ But, in a ‘bail-in,’ it is the depositors who lose. Their deposits are ‘converted’ to equity in the bank. When they try to sell their bank shares, they find that it will fetch only a fraction of the value of their deposits. A variant of this is what happened in Cyprus in the spring of 2013. Because of the distaste the public now has for ‘bail-outs,’ if there is another financial crisis, this is likely to be the method used;

- Default on Entitlements – when we talk about ‘entitlement reform’ in the U.S., we really mean at least a partial default. It is likely that some people simply won’t get what they were promised. We put this low on the list because we have witnessed a political process that won’t deal with the issue;

- Repudiate Debt – Because the government can simply print money to pay it debts, this is the least likely of all of the possibilities in the U.S.

The long-term issues are serious. And not addressing them simply means a higher level of pain when addressing them is required. Remember, these are long-term issues. They are all not likely to occur at the same time, nor will they simply appear overnight. The first signs of trouble will occur when markets begin to recognize that the ‘official’ inflation rate significantly understates reality, or that the inflation data become so overwhelming that they can no longer be masked. Even then, markets may come to tolerate higher inflation, as after 100 years of fighting inflation, the Fed and the world’s major central banks have embraced it as a good thing.

Meanwhile, as set forth in Part I of this paper, the immediate outlook for the economy is upbeat. Enjoy it while it lasts.

December 20, 2013

Robert Barone, Ph.D.

Joshua Barone

Andrea Knapp Nolan

Dustin Goldade

Part I: The Short-Term Outlook – A Strong and Accelerating Economy

Posted in Banking, business, Economic Growth, Economy, Federal Reserve, Finance, Housing Market, investment advisor, investment banking, investments, Markets, mortgage rates, Robert Barone at 4:41 PM by Robert Barone

Those who read our blogs know that over the past 6 months or so, we have turned positive on the underlying private sector of the U.S. economy. We have had comments from several readers about this apparent change of heart, some of them almost in disbelief. So, let us dispel any doubts. There is a huge difference between the short-term and the long-term outlooks. Let’s realize that long-term trends are just that, long-term, and that they take a long time to play out. As you will see if you read through both parts of this year end outlook, our long-term views haven’t changed. But, since the long-term doesn’t just suddenly appear, there really isn’t anything contradictory in being optimistic about the short-term. As a result, we have divided this outlook up into its two logical parts, the short-term and the long-term.

Let’s start with the short-term. First, at least through 2014 and probably 2015, the ‘fiscal drag’ that caused headwinds for the economy has now passed with the signing of the budget deal in mid-December. In his December 18th press conference, Fed Chairman Bernanke indicated that four years after the trough of the ’01 recession, employees at all levels of government had grown by 400,000; but at the same point today, that number is -600,000, i.e., a difference of a million jobs. Think of that when you think about ‘fiscal drag.’ The November jobs data shows that jobs at all levels of government have now turned positive. No matter your view of the desirability of this, those employees receive paychecks and can consume goods and services. So, from a short-term point of view, the ‘fiscal drag’ has ended, and, all other things being equal, this will actually spur the growth rate of real GDP.

Manufacturing and Trade

The institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) indexes, both manufacturing and non-manufacturing, are as high or higher than they were in the ’05-’06 boom period. This is shown in the chart immediately below.

Shown in the next chart is industrial production, which in November, finally exceeded its ’07 peak.

Now look below at the auto chart. Sales are as frothy today as they were in the pre-recession boom. Sales for the holiday buying period are destined to surprise to the upside.

Housing

Part of the reason that the economy is not overheating is housing. The chart clearly shows that housing starts are significantly lagging their ’05-’06 levels. But, recognize that ’05-’06 was the height of the housing bubble.

November’s housing starts surprised to the upside. But, they are still only 53% of their bubble peak. Nevertheless, because new home construction has been in the doldrums for the past six years, the resurgence evident in the economy has pushed the median price of a new home north of what it was then. In addition, the lack of construction has put the months’ supply of new homes at less than 3. In the housing bubble, when everyone was in the market, the average level of supply was 4 months. So, in some respects, the current housing market is hotter than it was at the height of the bubble. And, while interest rates have risen and are a cause for concern, they are still very low by historic standards, and we have a Fed that on December 18th recommitted to keeping them down for a period much longer than the market had anticipated.

Labor Markets

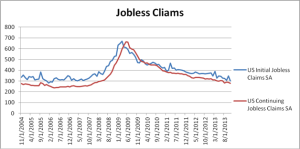

Because the popular unemployment index is a lot higher today than it was in the ’05-’06 boom (7% vs. 5%), the popular media assumes that the labor markets are still loose. But, demographics and incentives to work have changed over the past seven years. The labor sub-indicators imply a much tighter labor market than the traditional unemployment index would lead one to believe. Recent new nonfarm payrolls are equivalent to their monthly gains of ’05-’06. The weekly Initial Jobless Claims number for the week ending 11/30 was 298,000. Except for one week this past September, you have to go all the way back to May ’07 to find a number that low. The first chart below shows the definite downtrend in new and continuing jobless claims.

The next chart shows that layoffs and discharges are lower than they were in ’05-’06 and that both the “Job Openings” and “Jobs Hard to Fill” sub-indexes are in up trends and are approaching ’05-’06 levels.

The Aggregates

So, while auto sales are booming, the labor markets are tight, and manufacturing and services are expanding at or near boom levels, why do the aggregates (Real GDP, for example) appear so depressed? One explanation that we think has some credibility, is that there has been an expansion in the underground economy (barter; working for cash, etc.). The ‘fiscal drag’ headwinds discussed earlier, have, no doubt, had a large impact on the sluggish growth in the aggregates. On a positive note, the latest revisions to Q3 ’13 Real GDP show a growth rate of 4.1%, which, on its face, supports our short-term optimism. And until mid-December, the markets had discounted this as resulting mainly from growth in unwanted inventories. But Black Friday and Cyber Monday sales along with upbeat ongoing retail reports tell us something different, i.e., the inventory growth was not unwanted at all. While the markets expect a 2% Real GDP growth for Q4 ’13, don’t be surprised if it is much higher.

Short-term Implications

The underlying data, at least for the next 6 to 12 months, point to a strengthening economy. Certainly, a stock market correction is possible. We haven’t had one for more than 2 years. But, while possible, a significant downdraft like those of ’01 or ’09, don’t typically occur when the economy is accelerating (1987 is an exception) without an extraneous and unanticipated shock. With the signing of the first budget deal in four years, and with the Fed clearing the air about tapering and actually extending its announced period of zero interest rates, almost all of the short-term worries appear to be behind us, except one.

Inflation – The Potential Fly in the Ointment

The ‘official’ Consumer Price index (CPI) was flat in November, dominated, as it has been all autumn, by the fall back in gasoline prices. Somehow, while we all know that everyday prices are rising at a significant pace, the markets have bought into the deflation theme. Perhaps the belief is that if the markets play along with the Fed’s low inflation theme, the Fed will remain easier for longer.

In his December 16th blog, David Rosenberg (Gluskin-Sheff) has the following to say about inflation:

I have a tough time reconciling the ‘official’ inflation data with what’s happening in the real world… the .7% jump in retail sales in November on top of +.6% in October – these gains were all in volume terms? No price increases at all? Restaurants are now registering sales at a double-digit annual rate… No price increases here? The BLS tells us in the CPI data that there is no pricing power in the airline industry and yet the sector is the best performing YTD within the equity markets… global airline service fees have soared 18% in 2013… these [fees] are becoming an ever-greater share of the revenue pie and one must wonder if they are getting adequately captured in the CPI data.

Inflation could be the fly in the ointment for 2014. As long as the markets play along with the Fed’s deflation theme, as we expect they will as long as they can, the economy and markets will do just fine (this doesn’t mean there won’t be a correction in the equity markets, as we haven’t had a meaningful one for two years). But sooner, or later, something will have to be done about inflation. We will close this Part I with a quote from Jim Rogers, the commodity guru (Barron’s, October 12, 2013):

The price of nearly everything is going up. We have inflation in India, China, Norway, Australia – everywhere but the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. I’m telling you, they’re lying.

December 20, 2013

Robert Barone, Ph.D.

Joshua Barone

Andrea Knapp Nolan

Dustin Goldade

November 19, 2013

The Fed’s ‘Bizarro World,’ Part II

Posted in Banking, Big Banks, Bonds, Economy, Federal Reserve, Finance, Robert Barone, Uncategorized at 11:12 PM by Robert Barone

The Fed’s ‘Bizarro World,’ Part II

The “Seinfeld” TV comedy series (1989-98) had a set of episodes, known as “Jerry’s Bizarro World,” where everything “normal” was turned upside down and inside out. I have referred to this world in a previous column, and continue to find such Bizarro patterns in our real world.

The Fed was established in 1913 to act as a lender of last resort to a financial system that had been plagued with “panics” and deep recessions. At inception, its main policy tool was the “discount rate” and “discount window” where banks could submit eligible collateral to obtain needed liquidity when such options had dried up in the capital and financial markets.

Open market operations

Beginning in 1922, the Fed began to use a tool known as Open Market Operations (OMO), the buying and selling of government securities to add or subtract liquidity from the capital markets, reserves from the banking system, and to impact interest rates. OMO has traditionally been considered to be the Fed’s main policy tool. But that ended in late 2010 with the implementation of Quantitative Easing II (QE2).

In 2009, as the financial system was experiencing one of those financial panics, the Fed did what it was created to do, and provided liquidity to the markets where none was otherwise available. Many argue that Fed action via QE1 was instrumental in stabilizing the U.S. and world banking systems

Look at those excess reserves!

But, then, because the U.S. rebound from the ensuing recession was too slow, in late 2010 and again in 2012, the Fed announced more QE. Today, the latest figures show excess reserves in the banking system of $2.23 trillion. The reserves required on all of today’s existing deposits are $67 billion ($0.067 trillion). Today’s excess reserves are so massive that they can support 33 times current deposit levels without the Fed creating one more reserve dollar. Yet, with QE3, it continues to create $85 billion/month.

While they sit in an account at the Fed, excess bank reserves don’t directly influence economic activity. This, of course, has been the issue for the past five years. But, when banks do lend, the newly minted money gets into the private sector, impacting economic activity with the well-known “multiplier effect” described in money and banking textbooks. When such bank lending occurs, if the labor market is tight or there is little or no excess capacity in the business community, inflation ensues. Just think of how much money the banks can create if their current excess reserves are 33 times more than they need!

Sell side of OMO is impotent

So, how is the Fed going to control bank money creation in the future? They can’t use their most powerful traditional tool, OMO, because they would have to sell trillions of dollars of securities into the open markets before reserves would become a restricting issue for the banking system. The utterance of the word “tapering” last May sent rates up 100 basis points in a two-week period. This is just a taste of what would happen to interest rates if the Fed actually began to sell (instead of just buying a lesser amount, which is what “tapering” means).

Furthermore, long-term fiscal issues have become a real concern. With somewhere between $85 and $120 trillion of unfunded liabilities rapidly approaching as the population ages (as a comparison, annual U.S. GDP is only $16 trillion), huge fiscal deficits are a certainty barring entitlement, Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid reform. To keep the cost of the debt manageable within the U.S. government budget, the Fed must continue to keep interest rates low. With foreign criticism of U.S. policies on the rise, purchases of U.S. Treasury debt by foreign entities are likely to diminish in the future. That leaves the Fed as the major lender (lender of last resort!) to the Treasury via OMO purchases.

The borrowing window in reverse

Unable to use the “sell” side of OMO to influence the banking system, the Fed is now stuck with only one tool, the discount or borrowing window. Only now, because the financial system is drowning in the sea of liquidity, the borrowing window and discount rate must now work in reverse!

In the traditional use of the borrowing window, the Fed used the discount rate (short-term borrowing rate) to encourage (by lowering rates) or discourage (by raising rates) banks from borrowing to lend to the private sector. But, in today’s Bizarro World, the Fed will have to use the rate it pays (currently 0.25 percent/year) to the banks with excess reserves to encourage or discourage bank lending. Yes! Not the rate the banks pay to the Fed to borrow, but the rate the Fed pays to the banks to encourage them to keep their reserves instead of lending them. The original concept of the Fed as the lender of last resort has been turned on its head. It’s backward — it’s Bizarro!

Implications for investors

It is difficult for investors to deal with a system turned on its head. The bond market gets spooked whenever there is talk of the Fed “tapering” its bond purchases. The return on those bonds is simply too low for the risk involved, so the best advice here is to avoid them unless you are exceptionally skilled. That leaves equities — but that is a topic for another column in this new and Bizarro World.

November 5, 2013

The Fed is bungling world’s reserve currency

Posted in Federal Reserve, Finance, Uncategorized tagged Robert Barone (Ph.D. at 9:38 PM by Robert Barone

The Fed has proven to be a terrible caretaker of the responsibilities that come with reserve currency status, even while the U.S. economy benefits greatly from it. The bungling is so great that the dollar is now at risk of the loss of that status, and with it, those huge benefits.

Some history

After both world wars, the U.S. had the strongest economy. And despite FDR’s removal of the U.S. from the gold standard in 1933, the Bretton Woods agreements of 1944 established a “gold exchange” standard wherein balance of payment deficit nations were to settle up with surplus nations in gold (at $35 per ounce).

Under this system, when gold payment settlements were made, the gold never was physically shipped but simply “moved” in the holding vault to an area designated for the recipient country.

In 1971, Republican President Richard Nixon removed the world from the gold exchange standard when France demanded physical delivery. Since then, the dollar has served as the world’s reserve currency, with “trust” as the only underlying asset.

The perks of reserve status

Most international transactions today occur in dollars, even if none of the transacting parties is American. For example, if Hyundai (South Korea) sells autos to a business in Argentina, the buyer must first convert the Argentina peso to dollars to pay for the autos. Hyundai can either hold the dollars, or convert them to their home currency (Won).

Note that this transaction has little to do with U.S. economic activity. Yet, it means that there has to be a lot of dollars floating around to support worldwide trade.

The reserve currency status and trust in the U.S. dollar has resulted in the U.S. government’s ability to overspend and issue debt because of the demand for dollars in international trade.

On the other hand, when an emerging economy’s government runs a large and systemic deficit, there are serious fiscal consequences. The value of the currency immediately falls, inflation occurs and the markets force up interest rates, thus impacting that economy’s economic growth.

The reserve currency status and the accompanying trust in the currency also have resulted in the investment of excess dollars in the international system back into U.S. Treasury securities, allowing the Treasury to run large deficits without significant consequences for the currency’s value.

Emerging pressures

Of course, we’ve all heard stories that countries like China and Russia have been advocating that the world adopt a different reserve currency. Many dismiss China’s and Russia’s positions as political rants. But these gripes are legitimate, and unless they are changed, the existing monetary and fiscal policies in the U.S. eventually will move the world toward an alternative reserve currency system.

Policy impacts

While Congress has played a major role, the Fed in particular has been irresponsible as the caretaker of the world’s reserve currency. Because the U.S. never openly asked that the dollar be the reserve currency, the Fed maintains that its only interest is in America’s economic performance. But Fed policies, such as quantitative easing, have huge consequences worldwide.

For example, when the Fed tells the capital markets that interest rates will be 0 percent for an “extended period,” as it did in 2012, hedge funds borrow dollars at minuscule yields and send unwanted dollars to higher-yielding emerging market economies.

Those capital movements have been monstrous, often overwhelming the emerging economy’s underdeveloped financial system, causing inflation in the local economy along with rising interest rates and slowing economic growth.

Then, last May, when Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke used the word “taper,” those huge flows, which had built up over a period of months, almost instantaneously reversed as the hedge funds raced to repay their borrowings before interest rates rose further.

Robert Barone (Ph.D., economics, Georgetown University) is a principal of Universal Value Advisors, Reno, a registered investment adviser. Barone is a former director of the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco and is currently a director of Allied Mineral Products, Columbus, Ohio, AAA Northern California, Nevada, Utah Auto Club, and the associated AAA Insurance Co., where he chairs the investment committee. Barone or the professionals at UVA (Joshua Barone, Andrea Knapp, Matt Marcewicz and Marvin Grulli) are available to discuss client investment needs.

Call them at 775-284-7778.

Statistics and other information have been compiled from various sources. Universal Value Advisors believes the facts and information to be accurate and credible but makes no guarantee to the complete accuracy of this information.

June 20, 2013

Domestic and Foreign Events Are Tying the Fed’s Hands

Posted in Federal Reserve, Finance, Uncategorized tagged Debt, Deflation, Robert Barone at 10:29 PM by Robert Barone

NEW YORK (TheStreet) — Despite apparent emerging strength in the U.S. economy, the Fed is faced with serious consequences, if it moves toward a reduction of policy ease. Those consequences include:

• A potential violent market reaction;

• the quashing of the nascent private sector animal spirits;

• the short-term negative consequences of a stronger dollar on imports and exports; and

• the long-term issues of the size and cost of the debt.

The Wealth Effect

The “wealth effect” has been studied for decades with the universal conclusion that its overall economic impact is marginal; i.e., the wealthy simply have a low marginal propensity to consume. Yet, this appears to be the only benefit of the massive QE programs, which — as documented by two revered market pundits, David Rosenberg and Jeffrey Gundlach — has a nearly 90% correlation with the equity markets.

In recent weeks, we saw the violent reactions in both equity and fixed-income markets to the mere concept of “tapering,” which is not tightening, but simply less easing (a change in the 2nd derivative). Clearly, a move to lessen ease risks the small success that massive QE has had to date.

Deflation

Deflation is a worldwide issue, even among emerging industrial powers like the BRICS. China’s economy, which has been the world’s economic growth engine for the past half decade, appears to be slowing significantly, despite its official purported 7.5% growth rate. The underlying data tell the story, including depressed raw commodity prices, excess high seas shipping capacity, the value of the currencies of commodity-producing countries like Australia, and a falloff in exports from lower-cost producers like South Korea.

Except for Japan, in April, the IMF significantly lowered its growth forecasts for every industrial economy. Thus, any tightening move by the Fed would only exacerbate worldwide deflationary pressures.

Debt Costs

The high and rising cost of U.S. debt, much of which is financed by foreigners, makes abandonment of easy money highly risky for U.S. fiscal policy. The U.S. public is unaware that the true GAAP deficit has exceeded $5 trillion for the past five years. Instead, the $1 trillion cash-flow budget deficit is viewed as the issue. Nevertheless, as time passes, the already built-in additional $4 trillion per year of promises will become current obligations.

I have seen several estimates of the cost of that future debt in rising-interest-rate scenarios. None are pretty. The most recent from Jeffrey Gundlach of Doubleline estimated the cost of the debt and deficit at $2.5 trillion by 2017, if the 10-year rate were to rise gradually from its current 2.1% level to 6.0%. By then, Gundlach says, the debt itself will be $26 trillion. Such deficits and debt levels risk not only inflation, but the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency.

Conclusion

The consequences of rising U.S. interest rates are dire. They would exacerbate worldwide deflation, play havoc with the nascent U.S.economic recovery, reverse the limited positive impact of the wealth effect via U.S. equity markets and have dire consequences for the dollar and U.S. fiscal policy. Rising rates will inevitably occur, but don’t count on them anytime soon.

Robert Barone (Ph.D., Economics, Georgetown University) is a Principal of Universal Value

Advisors (UVA), Reno, NV, a Registered Investment Advisor. Dr. Barone is a former Director of the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco, and is currently a Director of Allied Mineral Products, Columbus, Ohio, AAA Northern California, Nevada, Utah Auto Club, and the associated AAA Insurance Company where he chairs the Investment Committee.

Information cited has been compiled from various sources which UVA believes to be accurate and credible but makes no guarantee as to its accuracy. A more detailed description of the company, its management and practices is contained in its “Firm Brochure” (Form ADV, Part 2A) which may be obtained by contacting UVA at: 9222 Prototype Dr., Reno, NV 89521.

Ph: (775) 284-7778.

June 4, 2013

The age-old challenge: Buy low or sell high?

Posted in Economy, Finance, Uncategorized tagged inflation, Money Printing, Robert Barone at 7:00 PM by Robert Barone

profits and to a stronger employment market.